Specialty Coffee Roasters in Colorado's Roaring Fork Valley

On its way to becoming coffee, coffee—momentarily—becomes something else.

“At about 280°, the beans take on a yellow color and the aroma of sweet hay,” says Jeff Hollenbaugh, co-owner of Defiant Bean Roasters, as we peek through the window of his 24-pound roaster in the company’s headquarters in an industrial garage on the outskirts of Glenwood Springs.

Hollenbaugh pulls a wood-handled scoop full of beans from the roaster and offers it to me. I inhale, and visions of fresh-cut alfalfa flood my mind. Inside the drum of the roaster, the beans continue to spin, growing darker by the second.

“By the time the roaster reaches 330° they’re cinnamon brown, and they smell a bit like baking bread,” Hollenbaugh says. He withdraws the scoop again, and the smell of fresh, crusty loaves hits my nose. There’s clearly more to these beans than meets the eye.

Coffee is everywhere at Defiant Bean Roasters—in the air, in 50-pound sacks stacked on pallets near the entryway, and in large plastic totes awaiting the attention of Hollenbaugh’s father, Gary, who weighs and bags the beans for shipping.

As he roasts, though, Hollenbaugh is immune to his surroundings, hunched over a small laptop wired directly to the roaster. The wire transmits temperature data from the roaster to a “roast logging” program that charts heat, time and important roasting milestones—the cracking of the beans, or changes in their color and smell. As a curve forms on the screen, Hollenbaugh tweaks knobs to adjust the roaster’s heat and airflow.

“You want to push the beans in different ways during different parts of the roast profile,” he says.

After a few minutes, the familiar nutty, caramelized smell of coffee fills the air. To Hollenbaugh, it’s one of several signs that his roast—a Sumatran and Guatemalan mix he calls “Blend X”—is nearly done. Coffee roasting comes in short, intense bursts; most roasts take between 10 and 15 minutes to complete.

“In the latter part of the roast, 5° of temperature difference can be everything,” Hollenbaugh says. He pulls open a hatch and the beans spill out into a metal basin, where they’re sifted and cooled by a rotating paddle. Hollenbaugh swivels toward the bags of beans in the corner, and he’s on to the next batch.

A Pleasure in Itself

Defiant Bean Roasters, which Hollenbaugh co-founded five years ago with his brother Brian, is just one of several small batch, specialty coffee roasters that have sprung up in the Roaring Fork Valley over the last decade. All are at the forefront of a growing global movement toward specialty coffee, which challenges the notion of the drink as a caffeinated productivity booster and embraces its potential as a pleasure in itself.

For some roasters, this is nothing new:

John Rose, a bear of a man with the protuberant nose of a sommelier, has been a partner of the Aspen-based ink! Coffee since 1998, and has roasted every pound of its beans.

Craig Fulmer, founder of the Carbondale-based Rock Canyon Coffee, started roasting five years ago when he was still a financial planner at a Boston insurance company, making him the relative newcomer of the bunch.

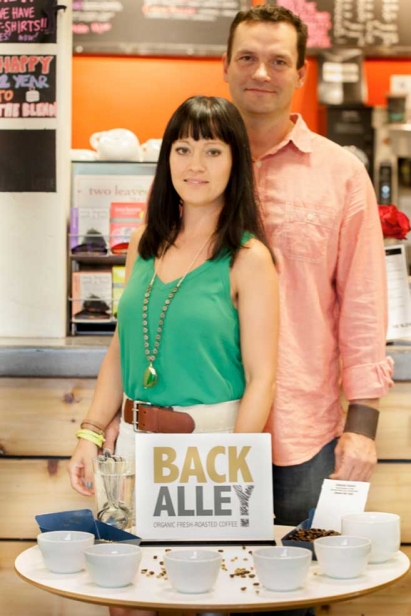

Back Alley Coffee, an outfit that started in Willits seven years ago, recently relocated to Main Street in Carbondale, and owners Jessica and Wade Droegemeier took over from Jessica’s dad, Steve, in 2011.

Local coffee shops also feature the wares of some of Colorado’s best roasters—The Blend Coffee Company in Carbondale serves the brew of Denver-based Novo Coffee, a 10-year-old outfit that’s earned a national reputation for sophisticated beans.

The specialty coffee movement’s central claim is that coffee deserves to be treated like wine, enjoyed for the terroir imparted by its native soil or the subtle notes imbued through careful roasting. (Coffee snobs are fond of pointing out that coffee has more aromatic flavor compounds than wine does.)

With its emphasis on celebrating the quirks of individual beans and highlighting the farmers who grow them, the specialty coffee world is a far cry from instant coffee, coffee “pods” and the swill in the office coffee pot. Its roasters and baristas speak without irony of the elderberry, blackberry, butterscotch and light jasmine notes in your cup–a cup of Novo coffee with all of those notes, in fact, is likely for sale at The Blend today.

Drink Globally

Coffee is a global commodity, a tropical plant that originated in Ethiopia but spread quickly¬ through human channels to every continent on Earth. The crop’s caffeine content has always been a central selling point: Rumor has it that Ethiopian goat herders discovered coffee’s value when they noticed their animals going berserk after nibbling on coffee trees. Today, Indonesia, East Africa, Central and South America and Hawaii all have their own distinct coffee varieties, and everyone along the product’s supply chain—farmers, importers, distributors, roasters and cafés—has the power to make or break what’s in your cup.

The best coffee grows at elevations of up to 6,000 feet: Coffee cherries mature more slowly at altitude, making their seeds—the coffee beans—harder, denser and more flavorful. Coffee is mostly harvested by hand, since the steep mountain slopes of many plantations make the use of mechanized equipment nearly impossible.

The way that beans are processed after harvest has a huge effect on their ultimate flavor: “Washed” coffees like those common in Kenya and Colombia are skinned, pulped and rinsed of their fruit immediately after harvest, giving them a clean and bright flavor. With “natural” coffees, by contrast, the cherry is left to dry with the skin and fruit intact, allowing the sugars of the coffee cherry to ferment and infusing the beans with fruity, funky notes.

Decaf coffee, Hollenbaugh says, is “mainly a pain in the butt” to roast, since the caffeine is leached out of the beans by bathing them in a caffeine-saturated solution, a process that leaves beans soggy and makes them behave erratically in the roaster.

“Once the beans dry out, they’re never the same again,” Hollenbaugh says.

Though a roaster’s real work begins when the beans arrive at his door, there’s plenty of advance work in sourcing the beans. Particularly for small coffee roasters, maintaining a tight relationship with importers is key. They help to navigate the complex and costly maze of international shipping, and they offer roasters a rotating slate of new beans to try.

While relying on importers for the bulk of their beans, some local roasters do cut out the middleman with certain coffees, forging direct connections with the farmers who grow them. ink! Coffee has a longstanding relationship with a farming family in central Brazil, and the proceeds of their bean purchases have been used to build a school and provide dental care to residents there. Back Alley Coffee sources buttery Kona coffee directly from a farmer in Hawaii, and the Droegemeiers are planning a trip to El Salvador this fall to visit coffee farms.

No matter how airtight the supply chain, strange things can happen on a bag of beans’ long journey.

“Quakers,” unripe beans with low sugar content, are a regular headache for roasters, and Rose says he’s discovered objects as alien as lizards, rocks, snakes and even unused bullets in his coffee beans. He keeps a collection of some of these curios at his Basalt headquarters, and keeps an eye out for more in every incoming bag.

With so many variables in play, there’s considerable trial and error involved in the roasting process.

“Every time I roast a new bean, I roast it light, medium and dark and cup it to see what I like,” says Fulmer. The mixture of art and science that roasting requires (Rose refers to it as a “highly unscientific science”) is a draw for many roasters.

“I love it because it’s a mixture of science and heart,” says Jessica Droegemeier.

Two Cracks

The two main benchmarks of the roasting process are the first and second crack of the beans—both are signs of moisture evaporation and bean expansion.

The first crack, when the bean sheds much of its “chaff,” or hull, occurs at around 380° and generally signals the beans’ transition to a light roasted phase. The second crack, which is caused by the line on the underside of the bean cracking open, happens around 420° and indicates a shift into “dark roasted” territory.

Although most beans require less than 15 minutes of roasting, the process does take slightly longer at altitude than at sea level, because of lower air pressure. Many Colorado roasters are proud to advertise this fact, claiming that longer roasting times give their coffee deeper, more complex flavors.

Even with a few guideposts to mark the roasting process, roasters are constantly checking and sampling their beans as they cook.

“You have to trust your nose and ears more than your eyes when you’re roasting,” says Fulmer, whose inspiration in the roasting world is Gerry Leary, a blind roaster who operates the Unseen Bean Coffee Company in Boulder.

One of the central injustices of coffee roasting is that, for all of the care and precision that goes into the process, roasters can’t control how their coffee is ultimately brewed. The quantity and grind of the coffee that’s used, as well as the quality and temperature of the water, are often left up to a barista or home drinker who may have a dim understanding of the long and laborious road the beans have traveled.

“We as roasters are at the mercy of the end preparer,” Hollenbaugh says.

To banish thoughts of ill-prepared coffee from their heads, all of the Roaring Fork Valley roasters drink plenty of their own product, and they make sure to brew it right. “[My husband and I] drink three or four cups of coffee per day,” says Droegemeier. “We have five kids between us, so we need the coffee.”

Hollenbaugh’s habits are similar, if more variable.

“Sometimes I’ll have one cup of coffee, and sometimes I’ll have eight,” he says. “It depends on the day!”

CUPPING: Sample Coffee Like the Pros Do

Cupping is used in every step of the coffee supply chain—it’s done on the farm by importers deciding what to buy, by roasters envisioning their own custom blends and finally by shop owners who want to ensure that their name is tied to a premium product. Here are the typical steps in the cupping process, with images from a recent tasting of Ethiopian beans at The Blend Coffee Company in Carbondale.

Grinding and weighing:

Beans are ground to a slightly finer size than the grind used for drip coffee, are weighed into doses of between eight and 10 grams and are poured into separate cups. To ensure freshness and full flavor, the coffee should be ground as close to the time of cupping as possible.

Sampling the dry aroma:

Participants inhale the aroma of the dry coffee grounds, to pick up qualities (both good and bad) that may not be evident in the final brewed product. “The aromatics of a coffee are the most volatile components,” says Jeff Hollenbaugh of Defiant Bean Roasters. “You will detect aspects of the coffee in the dry aroma that you may never find again as the coffee is brewed.”

Steeping the grounds:

Hot water is poured over the grounds all the way to the rim of the cup, so that the grounds form a crust. The coffee is allowed to steep for about four minutes. Coffee cupping protocols are highly standardized: The Specialty Coffee Association of America recommends that water be poured at a temperature of about 200° Fahrenheit.

Breaking the crust, and slurping:

Participants break the coffee crust with a spoon, inhale the coffee’s wet aroma, then loudly slurp a spoonful of coffee, taking care to distribute it over as much of their mouth as possible to experience the full complexity of its flavor. The spoon is rinsed before sampling a different bean. Pictured here are Wade Newsom of The Blend Coffee Company and Jeff Hollenbaugh of Defiant Bean Roasters.

GO FIND IT!

The Blend Coffee Company: TheBlendCoffeeCo.com

Defiant Bean Roasters: DefiantBean.com

Rock Canyon Coffee Roasters: RockCanyonCoffee.com

ink! Coffee: InkCoffee.com

Back Alley Coffee: BackAlleyCoffee.com

Novo Coffee: NovoCoffee.com