Fire Lines

Last summer the Grizzly Creek Fire exploded through Glenwood Canyon, where the Nieslanik ranching family had cattle grazing on a Forest Service permit. With such dangerous conditions, they were forced to leave their cattle to fend for themselves—amazingly, none were lost. As Jim Nieslanik speculates on how their cattle survived, he shares contours of specific drainages, illustrates exact steep ridges, and describes open meadows by name. It’s a poetic intimacy with local topography few could match.

But it’s more than poetry: This frontline knowledge of geography and grazing habits may also be the key to future fire mitigation, climate adaptation, and by extension, the resilience of our local food system.

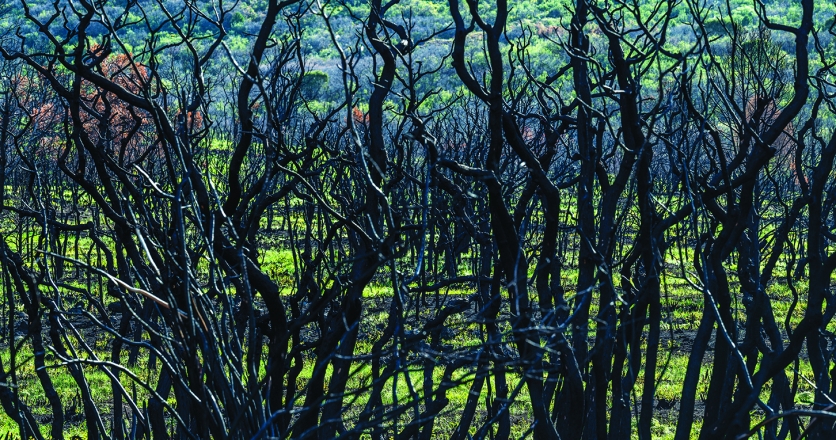

Across the West, climate change and increasingly devastating wildfires are the unsettling new normal. In 2020, Colorado saw the three largest wildfires in state history. Drought and the lack of regular monsoons mean hotter and drier weather than ever such that, according to Becca Samulski of nonprofit Fire Adapted Colorado, we now have a year-round fire season. Conditions like these put agriculturalists— and thus, local food—at unprecedented risk. To inform this piece, I turned to some of the Roaring Fork Valley’s historic ranching families—Nieslanik, Fales, Perry, and McNulty—who have been raising and grazing beef here for a century or more. It was immediately clear that the climate they ranch in would be unrecognizable to their ancestors. Yet with livelihoods tied to a reciprocal relationship with nature, ranchers may hold solutions for building resilience in a rapidly changing world.

Good disturbance

It’s not simple, according to Robin Young of CSU Extension. Pressure to overgraze combined with historically heavy-handed fire-prevention tactics have led to severe environmental problems. Now it’s time to flip the script, says Young—not all fire or grazing is bad. Unmanaged, both can degrade land and contribute to dangerous climatic forces. Intentionally managed, they become critical tools in building climate resilience—decreasing fire risk by clearing fuel loads, restoring native plants, and improving the soil.

Rangeland environments co-evolved with disturbance, be it migratory herds of ruminants—think buffalo or elk—or low-intensity wildfires. Samulski explains: “When we disrupt those processes, or aren’t managing them wisely, we’re creating conditions for the wrong type of fires. But grazing is another form of combustion—a much slower chemical process than fire. In a lot of ways, they’re doing the same things: turning that food into waste and carbon dioxide and breaking it down. These are essential processes.”

In other words, we need ranchers and their livestock. Our previously open lands are now so fragmented that these natural processes can’t fully occur.

But right now, ranchers are just trying to survive: “Imagine trying to evacuate 100 cattle with a fire coming,” says rancher Katy McNulty, who faced that issue when the Panorama Fire swept through Missouri Heights in 2002. “I ran to cut fences to give the cows a place to get out. You’ve got to just get yourself safe. It’s frightening.”

Already she’s been impacted by three major fires, each worse than the last—leaving scorched fence lines and grasslands that struggled to recover. McNulty, who can trace the genetic lineage of her cattle back to her great-great-grandfather’s herd, feels uncertain about her ranching future due to climate change, and that uncertainty will likely only intensify.

When I ask each rancher about their disaster preparedness, evacuation plans, and community support systems, they shrug off the questions—drought is the more immediate threat. “In the last 10 years, the winters have less snow and have gotten warmer,” Nieslanik says. “We’re losing our deep moisture in the ground. Sometimes we run out of water in our creek in the middle of June.”

Each lamented a hay harvest last year that was just 25 percent of average. Less water translates to fewer irrigated fields, which also act as important fire breaks. Less local grass means a decreased capacity to grow cattle, forcing ranchers to either import expensive hay or considerably cull their herd. Combined with increasing development of pastureland and decreasing beef prices, the climatic disruptions threaten to make ranching here unsustainable.

Hearing these stories, it’s hard not to feel the ache of shared loss, not only for local food production but also for the history, culture, knowledge, and profound reverence for this valley these ranchers hold. But there are ways forward.

Why ranchers are essential

After his family ranch near Montrose came close to ruin from land degradation, rancher Jim Howell posed the question: “Could ranchers help reverse these devastating global processes, while creating a triple bottom line?” Today, his company, Grasslands LLC, manages thousands of acres worldwide, using holistic grazing techniques to heal our grasslands.

Howell sees ranchers as essential: “As pastoralists, we’re key players in mitigating climate change because we have access to huge extensions of country: 40 percent of the world’s surface area is composed of rangeland environments, many of which are too cold, hot, steep, rocky, or dry to raise crops. The only way we can produce human food from these landscapes is by upcycling those native plants into high-quality animal protein.”

In Colorado, the Grasslands team is practicing techniques championed by ecologist and holistic management proponent Allan Savory: portable electric fencing to move higher densities of cattle quickly through smaller parcels of land—which mimics the natural wildlife-grazing patterns these rangeland ecologies depend on—and driving cattle into steep, hard-to-reach ridges and dense hillsides that, left alone, build dangerous fuel loads. By expanding the fodder range for their cattle, they can also sustainably increase the number of cattle on less land, increasing economic viability.

This knowledge of producing food while building resilience on the terrain ranchers use evokes Jim Nieslanik’s intimacy with local lands and inherent grazing wisdom—and it feels clear the foundation for a shift to holistic grazing is already there.

“We can manage livestock in ways that actually enhance biodiversity, the integrity of the ecosystem processes, and improve the water cycle,” Howell says. “We can even do a great job of increasing forest health and wildlife habitat, and mitigating fire risk.”

Certainly, not all ranchers can or will get there, and they’ll need external support in transitioning. Increasingly, though, young people are attracted to holistic management, says Howell, and even some of the oldest ranchers I spoke with have begun experimenting with these same techniques.

In addition to investments needed on the production side, McNulty reminds us of one familiar way Colorado consumers can help: by buying local. Be discerning, though, McNulty says: Support ranchers whose livelihoods depend on ranching, and who are truly invested in stewarding our collective resources. And, keep ranchland in agriculture.

Howell finishes, “You make a decision every day by virtue of what food you buy. Eat from your mountain valley, from cattle finished on that slope you can see outside your window. Invest in those resources.”

With so much potential, it’s fair to wonder, can we galvanize and sustain a way of ranching that builds resilience for all of us? I believe so, once we see ranchers as a critical part of the solution. ❧