The Meat of the Matter

Steakhouses have long conjured an aura of romance, sophistication and decadence—surely I’m not the only one who gets a jones for martinis and a ribeye watching “Mad Men” reruns. The flip side of steakhouse envy is intimidation—when you’re paying into the triple digits for a cut of meat, it helps to know what exactly you’re ordering with regard to different cuts, but if you understand the basics of cattle anatomy and meat grading (more on that in a minute), you’ll know which cuts are most flavorful and coveted.

The USDA evaluates meat according to “official grade standards” or quality assessment based on “tenderness, juiciness and flavor,” which is largely related to the amount of marbling, or fat intermingled with lean meat. Beef graded as Prime has the most prolific marbling and comes from younger animals—usually 30 to 42 months of age.

Most conventionally-raised beef cattle are finished on grain (usually corn) in feedlots—it’s this critical finishing time and supplementary feed that develops marbling, and thus flavor. Grassfed beef isn’t popular on steakhouse menus because it’s lower in fat and thus not as tender or flavorful, and the American palate still favors grain-finished beef (for more on grassfed cattle ranching, read our profile on Carbondale’s Milagro Ranch).

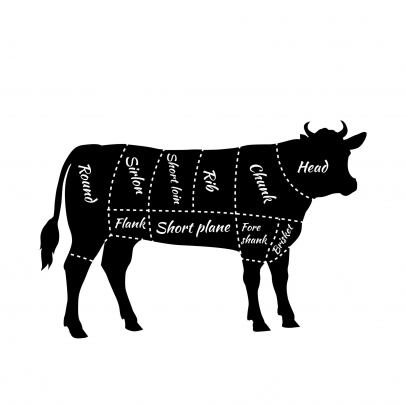

Understanding cuts will also enhance your steakhouse experience—for the purposes of this post, I’m only referring to beef. The carcasses are broken down into primal cuts—large sections like the loin or rib that are then cut into smaller portions known as sub-primals, like ribeye or top round.

The location of a cut generally determines its flavor and texture, which dictate the best methods of preparation. For example, the short loin is a sub-primal cut from the saddle area beneath the ribs—the origin of the most in-demand, pricey steakhouse cuts like Porterhouse and T-bone, which are best prepared broiled or grilled (depending upon thickness). These cuts are tender and succulent, because this muscle group isn’t used as much as a working muscle like the chuck, or shoulder. Tougher cuts from that region or the rump are best braised or stewed—“low, slow” cooking methods that require liquid, which breaks down the proteins in the meat. Tough, thin cuts like flank steak are best marinated, which also tenderizes the meat, and cooked quickly in a hot pan or on the grill.

The degree of doneness can also cause confusion. As a customer, you’re entitled to have your steak prepared the way you like it, but there’s a reason why chefs serve or recommend certain types and cuts of meat be cooked to a specific temperature. Executive chef Barry Dobesh of Aspen’s Monarch and Steakhouse No.316 (owned by Craig and Samantha Cordts-Pearce of CP Restaurant Group) explains it perfectly. “My opinion is that since we’re serving such high-quality Prime meat, it’s our preference to cook it medium-rare to medium, which best showcases its flavor (which is related to its fat and moisture content).”

Speaking of flavor, some steakhouses dry-age their beef, a centuries-old method in which large cuts are aged in a humidity- and temperature-controlled environment for weeks to months before being cut into portions. This allows the meat to tenderize (technically, the proteins are breaking down) and become more flavorful. Dry-aging requires space as well as time, hence the high price tag. A newer technique is wet-aging, in which the meat is matured in vacuum-sealed bags for a shorter period of time.

Aspen’s sister steakhouses

Recently, I dined at Monarch and Steakhouse No.316. The two restaurants are successful in part because they have completely different décor and vibes, as well as distinctive bar programs and menu variations. Another key reason for their success is that they serve Prime American beef.

Monarch, styled after a London gentleman’s club, has a sedate, masculine vibe with touches that reflect Craig’s South African upbringing (mounted kudu horns, the presence of bunny chow— a beloved dish consisting of curry served in a hollowed out loaf of bread—on the menu). 316 is located in a historic 19th century home, with a seductive Western hunting lodge ambiance, and happening bar scene.

A steakhouse is only as good as its food and drink, however and the Cordts-Pearce’s, Dobesh and bar managers Ishael Ananda and Keith Goode excel (Monarch has a destination-worthy Manhattan menu that will lure even the staunchest vegetarian). Besides those Prime steaks, there’s other meat and seafood, in addition to updated steakhouse classics, from sauces to sides like Boursin creamed spinach, a tableside Caesar that’s the best version this side of Tijuana and decadent wild mushroom Parisian-style gnocchi. Both restaurants also have abbreviated, well-priced bar menus beloved by locals.

As much as I love steak, I rarely eat it, preferring to indulge when I have the opportunity (or funds) to order a Prime cut. At Monarch, I savored every mouthful of a juicy boneless ribeye with a perfectly seasoned crust, paired with a Burning Man Manhattan (cherrywood smoke, sweet vermouth, barrel-aged bitters and Eagle Rare). Some things are simply worth waiting for.

Want to learn more about decoding steakhouse menus? Check out this steak chart. This guide to sub-primal cuts and how to prepare them will help you purchase and prepare beef at home.