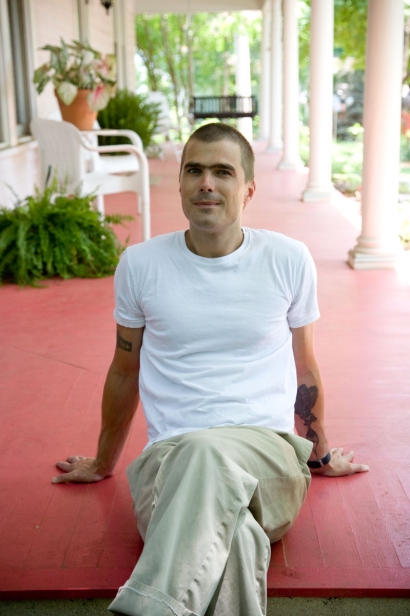

Getting Schooled in the Kitchen with Hugh Acheson

Fans of “Top Chef” will have no trouble recognizing frequent guest judge Hugh Acheson. The 42-year-old, Canadian-born, Athens-Georgia-based chef with a penchant for quippy comments may have come into the public eye thanks to his onscreen personality, but he’s no slouch in the kitchen either.

A 2002 Food & Wine Best New Chef, James Beard Award–winner, author and in-demand presenter at Aspen’s annual Food & Wine Classic, Acheson is also making a name for himself as an impassioned advocate for food security and culinary education. Here’s what the executive chef and co-owner of three of the South’s most revered eateries (Empire State South in Atlanta and Five & Ten and The National in Athens) has to say about his growing restaurant empire, his love for Southern cuisine and his passion for teaching kids to cook.

edibleASPEN: With regard to supplying your restaurants, how do you reconcile the conflict of meeting supply and demand with quality, seasonality and supporting your community?

Hugh Acheson: Well, my ethos is “Local first, sustainable second, organic third.” I want to support my community as much as possible. I get to encourage local farmers to grow better and smarter and help create demand for specialty products like sorghum. But something like garlic—it grows well here, but only for a short time. Yet I need garlic. Do I want to buy garlic from Gilroy [California] or China? I source it from Gilroy, because at least I’ve been there and know the farming practices behind it. It may be agribusiness, but at least I’m researching it. I’m not trying to solve the world’s problems, I just want to make a difference. I encourage everyone to think through their food purchases a bit more. We don’t need to buy everything locally, but small steps are great.

eA: To that end, you’re passionate about food security. What are you personally doing to strengthen your local foodshed and change food policies?

HA: I want to get people cooking from scratch again, and teach kids to eat better at a young age. Getting a 4-year-old to eat beets is an easier job than convincing a 12-year-old. We need to change what America equates as food. KFC needs to be viewed as an unhealthy treat once a month, not a daily meal. It can’t be perceived as the best value, so I’m invested in teaching kids life skills in the form of cooking.

eA: Can you elaborate?

HA: I have a team of like-minded chefs and hospitality people working on revamping the home economics curriculum in our local schools. It started after my daughter, Beatrice, who’s 12, came home from class and told me they’d made bacon-wrapped chocolate croissants, using processed ingredients. Ugh. You could instead teach a kid to make a salad dressing and save them thousands of dollars in a lifetime. Right now we’re working with school superintendents and state government—the infrastructure is already there and we have teachers who are ready, willing and able to teach new skills. Kids are such sponges, eager to learn.

eA: You had a partly rural upbringing. How has that influenced your views on educating kids about food?

HA: We ate canned goods like everyone else, but we also understood seasonality. At our cottage north of Toronto, we’d pick berries and make jam. We’d wait for corn season, then make relish. Teaching kids to make dill pickles from scratch eliminates the need for the existence of the pickle aisle at the grocery store. If I can teach them to pickle, grow or preserve a tomato, make an omelet, scramble an egg, make soup, I’m giving them life skills that provide them an alternative to the dollar menu at McDonald’s. Instead, they can say, “I know how to feed myself and four people in my dorm for under $10.”

eA: Was this the motivation behind your new book, Pick a Pickle: 50 Recipes for Pickles, Relishes & Fermented Snacks?

HA: Yeah, although it’s more of a booklet. It’s meant to get people thinking about the way food is made and the history of food preservation, as well as inspire them to get into the kitchen. There are a lot of classic Southern recipes, as well as modernist things. For example, Korean immigrants have had an influence on the “New Southern” cuisine, so I included a kimchi collards recipe.

eA: Tell us about your new restaurants, The Florence and Cinco y Diez.

HA: We decided to locate The Florence in Savannah, because it’s such a beautiful city, and the food scene is still developing. It’s located in a former ice factory, and the concept is an Italian restaurant showcasing Southern ingredients. It gives us an opportunity to source local seafood and product from the burgeoning organic farms in the area.

eA: Was the cuisine inspired by your travels?

HA: That, and conversations with a friend of mine, and one of my partners, Kyle Jacovino, who’s also the chef. Italian and Southern food get a bad rap for being heavy and laden with meat and fat, but in actuality they’re more agrarian than that, and based on seasonality. We’re focused on regional Italian dishes from the coast. There are 92 seats in the dining room, a coffee shop, an upstairs cocktail bar and a beer garden.

eA: And Cinco y Diez? How did a neighborhood cocina in Athens come about?

HA: It was my joke about what to do with the original Five & Dime space (after the restaurant relocated) if I couldn’t lease it. Somehow, my jokes usually become reality, so we opened a Mexican restaurant featuring local ingredients, called Cinco y Diez.

eA: As a veteran restaurateur, do you find it challenging to execute menus featuring cuisine that isn’t second nature to you?

HA: I’m excited by it every day—I love the idea of never getting bored with food. It gives me and my chefs the opportunity to research and cook and learn, and enables us to put menu items in front of customers that they haven’t seen before. They get just as enthusiastic about it as we do. It’s a feel-good scenario.

eA: What is it that excites you about Southern food?

HA: That it hasn’t ceased being defined. That it continues to have credence. That it’s based on seasons and vegetables, when we really look at it, and not diabetes and lard. It’s funny that we think of it as such an old food culture, but compared to Europe or Asia, it’s not. Southern food continues to evolve.

eA: How can our readers incorporate a Southern sensibility into their cooking here in Colorado?

HA: I think the concept of a “meat and three” is always a keen thing to look at. It means a small amount of meat and three vegetable dishes around it. That sort of needs to be the new way we do food: a reinterpretation of the classic Southern lunch. Say you have some fried chicken, and add a bit of chow-chow [a vegetable relish], a summer tomato or arugula salad, some crisped okra. And that’s a plate.

eA: At the 2014 Food & Wine Classic, your cooking demo is called “Best of the South.” What does this involve?

HA: My presentations are meant to be relatively heartfelt and encouraging of people delving into their community, wherever it may be, and learning about it, along with the food traditions of the area. I see my job as teaching people how to get immersed in that, and excited about food. I think we all need to be re-convinced that the best times we’ll ever have in our lives are cooking with our families, having a Sunday afternoon in the kitchen, everybody just hanging out and contributing.